Arrays and off-by-one

Bug in computing is an interesting word.

It has been constantly used within computing in particular contexts that

it has become highly intuitive, however, it lacks of a formal definition.

In [1] bug is defined

as

a deviation between the expected behaviour of a program execution

and what it actually happened

.

The definition is not entirely formal because it is not stated how

expectation is expressed.

Moreover, this definition relies on our ability to actually detect the divergence:

What about if there is a small, tiny deviation in the outcomes of a simulation

process that accumulates overtime but 'looks' right at each step to the naked eye?

it would be nice to detect a bug in a fly control unit before a space ship

crashes on landing, right?

On the other hand, if any expected behavior could easily be specified

formally, it stands to reason that it should be easier or almost effortless

to derive a software that complies with that specification.

Formal models fulfill a semi-automatized generation of programs with

(some) correctness guarantees.

In 1996 Woodcock and Davies [2] suspected that these kind of formal models

would become standard practice in software engineering.

So far, almost 30 years later despite showing advantages, e.g.

[5], [6], formal models are not at all mainstream practice

nor their parts, e.g. specification languages [2], [4] or

proof assistants [3].

Lately significant attention has been given to formal models in conjunction with

LLMs: [7], [8], [9].

An (untold) advantage of Formal Models is the possibility to clearly separate

design from implementation.

To implement a design in a formal model, you do not need to solve design problems

just be able to translate what is in the specification into the target language.

Likewise to create designs you do not need to know every aspect of an

implementation language, but know how to create models and prove their properties.

Nowadays, the typical job ad for a programming position asks for

problem solving

skills.

The programmer not only programs but also solve problems at different conceptual

levels, the role of the programmer is to design a solution and implement that

solution.

Relying on code comment and probably not well-curated documentation, this

approach hinders software evolution;

new employees must not only understand the code within the context of what

the code "should do" but also understand the "big picture" of how a component

fits and interacts with the others, knowledge that may be largely lost as

employees change roles or companies.

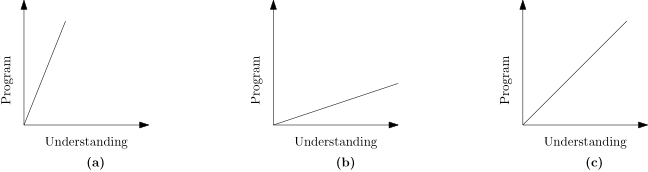

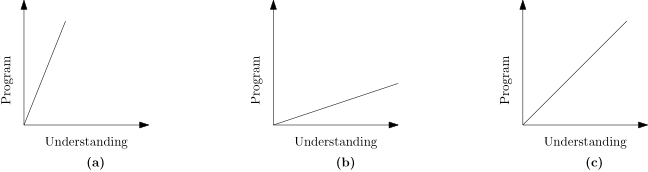

The following image depicts this behavior.

As time goes on, software evolves and in theory so should our understanding

of it.

Image (a) depicts when the software works but we have no idea why it works,

image (b) depicts when we believe we understand what the software does but

it actually does something different.

Finally, image (c) depicts a formal model driven development: understanding and

software evolve at the same rate.

However, using formal models to construct more correct software is not an easy

undertaking.

It is time consuming and sometimes a requirement change might break

a considerable part of the design.

Some approaches aim to promote reuse to derive faster proofs [10].

In this fifth part, inspired by off-by-one errors in C arrays, we develop a

framework to model arrays and various types of array concatenation that do not

introduce off-by-one errors and following the PwP series, it is amenable with

rewriting.

Off-by-one errors in programming occur when in a bounds calculation the result

is either one unit bigger or one unit smaller than it should.

At the CWE site

there are a few examples one of which I'm interested to see if can be modeled

using the machinery we have developed.

Let's take one example from CWE:

char firstname[20];

char lastname[20];

char fullname[40];

fullname[0] = '\0';

strncat(fullname, firstname, 20);

strncat(fullname, lastname, 20);

The strncat function takes three arguments, the first is the string (array)

where the concatenation will take place, the second is the string (array) that

will be concatenated at the end of the first and the third is the maximum number

of characters that will be copied.

The pinch of salt is: consider the call strncat(t,s,count); then t must

have at least count+1 available spaces because it will copy at most

count elements from s to t and add a terminating character at the

end of the copy.

Hence, the first call: strncat(fullname, firstname, 20); may write, in the

worst case, 21 characters into fullname.

When the second call is executed fullname[20] will be overwritten by the

first character of lastname and then copy at most 20 characters and write

the terminating character at fullname[41]; which is incorrect.

The solution as (CWE suggests) is to define the calls to strncat in terms of

the space available on the target string minus one to write the string

terminating character.

For this particular code the first call can be changed to: strncat(fullname,firstname, sizeof(fullname)-strlen(fullname)-1).

This works because fullname is

well-defined

at compile time, however,

if it is defined at run-time (heap allocated) this doesn't work.

The previous analysis rests on the logic of

what could happen

which does

not align well with the logic of

what should happen

.

The names of the arrays: firstname,lastname, fullname, lead the

reader to believe all three should hold valid strings, that is, a

succession of chars that end with a '\0' character.

However, in the worst-case analysis, this condition is completely neglected.

A careful reader might ask: "Why is the problem at the concatenation and not at

how firstname and lastname are defined?"

If firstname and lastname are

conventionally

correct strings,

then the example does not have any bug.

strncat stops copying once it encounters '\0' in the source, since the

sources are

conventionally

correct strings, at most each has 19

characters.

Hence, in total at most 38 characters would be copied into fullname leaving

space for the null-terminating character inserted by strncat.

This reasoning of

what should happen

shifts the blame from the

strncat portion to the correct construction of firstname and

lastname.

My personal point of view (contrary to the CWE's) is that this code should be

considered correct and if an error is detected, then the root cause is at how the

source variables are defined.

The CWE explanation and final solution is to read one character less from

lastname.

Arguably firstname and lastname are user-provided data, or data procured

from somewhere.

It is more important to attempt to preserve data than

silently

loose it.

Finding out some used-data is lost when there was no hard need is annoying to

say the least.

The best solution would be to simply make fullname bigger by one byte!.

Arrays can be modeled as a special kind of functions, similar to the one used

in alph: one side must be an index set usually from

to

and

the other side the 'data'.

We can wrap this into the array[N]

type

.

More formally, if d:array[N] then d(i,d_i) is defined for

and d/2 is a function.

If we distinguish an element ∅ from d's ddomain_right/1 then

we can define the

dlength

of d:

iff

then

.

Having defined length we can ask questions like: which array is the longest,

which is smallest.

We can also ask if it is possible to append a maximum number of elements from

one array at the end of another such that dlength/1 remains well-defined.

We can define djoinable/1 as djoinable(L):- size(N),dlength(AL), L + AL< N-1. where size/1 is the definition of the array's size.

Since we wish dlength/1 to remain well defined after the join, the place with

the special element (d(j,∅)) must be rewritten by the first element

in the join and after appending the remaining L-1 elements at least one

place must be available to write ∅, so we can think about the

< N-1 as reserving that place.

With just this machinery we can already see the CWE code is not correct, we can

model the code as:

:- assert(size(40)),

assert(dlength(0)),

djoinable(20),

retract(dlength(_)),

assert(dlength(20)),

djoinable(20),

retract(dlength(_)),

assert(dlength(40)).

This succession of calls with evaluate to no.

The assert/1 and retract/1 predicates modify Prolog's knowledge base.

This procedure can be generalized to an arbitrary number of queries without much

trouble.

I am tempted to already recognize array[N] as a

type

much with a

feeling of a dependent type [11].

However, its straightforward adoption implies a few changes that would not be

clear and which should not remain implicit, for example: database update.

A sbrelation relation

does not get modified during the execution of any of the predicates.

Now we can look a bit closer into this: it means that no predicate modifies the

relation (which perhaps would be better stated at the predicate level) but also

that the relation itself is not modified outside while a predicate is being

executed, that is, it is

thread safe

.

We have two clear and distinct dimensions: thread safety and mutation by

predicate.

We can address mutation by predicate with a new

type

dbrelation

which stands for dynamic binary relation (and leave thread safe

relations for later when we need them).

The possibility of modifying a relation opens a lot of venues.

Until now if we need to produce a result of an unknown length we used lists to

hold the values, now, dbrelation opens the possibility to create and

modify existing relations.

For example, now we can implement maps and fold predicates much like in a

functional programming language.

Actually, such functions can also exist in the sbrelation realm but the

results would be held in a list or variable; making it less clear but

operationally possible (perhaps it would be a good idea to add them at some

point).

We can define dadd(A,B):- \+ d(A,B), assert(d(A,B)). that adds the fact

d(A,B) to the database, ddel(A,B):- d(A,B), retract(d(A,B)). that

deletes d(A,B) from the database.

The predicate dadd/2 first makes sure the fact d(A,B) is not in the

database, likewise ddel/2 first makes sure the fact d(A,B) is in the

database.

We can generalize this a bit more with

conditioned

addition and

deletion: dcadd(P,A,B):- call(P,A,B), dadd(A,B).

dcdel(P,A,B):- call(P,A,B), ddel(A,B).

Where P is a user predicate that succeeds if the fact can be added (removed)

to (from) the database.

This goes beyond the mere presence of the fact in the database and allows us to

define conditions upon which we can manipulate the database.

We can implement a predicate that maps a given predicate over d/2 and create

the relation e/2:

dmap(P):-

forall(d(A,B),

(

(

call(P,d(A,B),e(C,D)),

catch(\+ e(C,D),_,d(A,B)),

assert(e(C,D))

)

;

(

call(P,d(A,B),pass).

)

)).

Looking closely, we were able to write a version of folding from the start:

dfold(P,IVal,R):-

bagof(d(A,B),d(A,B),Database),

plain_fold(Database,P,IVal,R).

plain_fold([],_,R,R).

plain_fold([D|Rs],P,IVal,R):-

call(P,D,IVal,Tr),

plain_fold(Rs,P,Tr,R).

This fold is fully useful only when the order of d/2 facts do not

matter.

If they are added into the database in such a way that the order in which

bagof/3 retrieves them is known in advance, it is possible to use

dfold/3 with predicates that depend on the order, however, this depends too much

on the particular implementation and it goes against the whole spirit.

Array concatenation (note the word

array

and not string) does

offer a bit more than meets the eye.

Before we can concatenate an array at the end of another, we must first be able

to determine its

length

.

The length of an array will be defined as the number of consecutive elements

in the array from the beginning (a(0,_)) up to a special element (nil).

We can define the special element by the predicate right_sentinel/1 like:

right_sentinel(nil).

So, if a(i,nil) is the entry with the smallest i, the length of a

will be i:

array_length(L):-

right_sentinel(S),

afold(min_entry(S),undef,L).

Where afold/3 is a rewrite of dfold/3 to work with a/2 and

the fold predicate min_entry/4 is partially defined.

As its name suggest it finds the entry with the special element and the lowest

index.

The first concatenation type we define is "Blind Constrained

Concatenation" array_bcconcat/1.

array_bcconcat(C) concatenates at most C elements of b/2 into

a/2.

It assumes a/2 is of 'infinite size', in other words, a/2 is big enough

to hold the new elements.

It doesn't check if b/2 has at least C elements but it stops early if

b(i,nil) is found.

We also require that array_length/1 remains well-defined.

array_bcconcat(C):-

C > 0,

array_length(TrgLen),

right_sentinel(Nil),

bmap(array_append_elem(TrgLen,C)),

NilPos is TrgLen + C,

mark_end(NilPos,Nil).

The concatenation itself is performed by bmap/1 which is dmap/1

rewritten to work with a/2 and b/2.

The predicate array_append_elem/4 is responsible to define the new a/2

entries and do nothing if b(_,nil) is seen.

The last mark_end/2 is a rewrite of dadd/2 to ensure array_length/1

remains well-defined.

At first glance array_bcconcat/1 might seem sloppy because it doesn't sound

to be a good idea to not check b/2.

There is an interpretation of this: Just as we assume that a/2 is

big enough to hold the result, we can assume b/2 is defined accordingly.

However, when we don't know if b/2 is defined as needed, we can use:

"Constrained Concatenation" array_cconcat/1.

array_cconcat(C):-

barray_length(SrcLen),

(

SrcLen >= C,

array_ucconcat(C)

;

SrcLen < C,

array_ucconcat(SrcLen)

).

array_cconcat(C) checks first if b/2 has enough elements and calls

array_bcconcat/1 accordingly.

barray_length/1 is a rewrite of array_length/1 for b/2.

The next type of concatenation is "Hard Stop Blind Constrained Concatenation"

array_hsbcconcat/1.

array_hsbcconcat(C):-

hard_right_sentinel(a(Pos,_)),

ConcatLimit is Pos - 1,

array_length(TrgLen),

(

ConcatLimit - TrgLen < C,

CopySize is ConcatLimit - TrgLen,

array_ucconcat(CopySize)

;

ConcatLimit - TrgLen >= C,

array_ucconcat(C)

).

The argument of the predicate hard_right_sentinel/1 marks the physical end

of the array, Pos is the size of the array.

Unlike right_sentinel/1 it is not meant to be moved around, so, the

expected used of hard_right_sentinel/1 is a position of the array with an

irrelevant assignment.

array_hsbcconcat/1 adjusts the maximum number of elements to be copied with

respect the size of the a/2 array assuming b/2 has enough elements and

ensuring array_length/1 remains well-defined.

Finally we define "Hard Stop Constrained Concatenation" array_hscconcat/1

that takes into account the size of a/2 and the length of b/2.

In other words, it is the safest concatenation when we don't know the

characteristics of a/2 and b/2.

array_hscconcat(C):-

barray_length(SrcLen),

(

SrcLen >= C,

array_hsbcconcat(C)

;

SrcLen < C,

array_hsbcconcat(SrcLen)

).

So far the rewrites we have explored seem to be a kind of external

application: we see something that can help us and rewrite predicate(s) that use

d/2 to work with our setting, e.g. graphs or Caesar cipher.

array_length/1 uses this kind of rewrite in the definition of afold/3, the

rewrite can be described as:

fold the list made from all the a/2

elements

.

However, the definition of barray_length/1 seems to be a bit strange.

To start with, it is a rewrite of a basic predicate to be used in the

same module (.pl file) where the basic predicate is defined.

At the same time, this basic function depends on a rewrite, and another

basic predicate (right_sentinel).

This shows that we must be careful when performing the rewrite, e.g. we must be

able to trigger the rewrite of afold/3 but with the

correct

arguments, i.e. instead of rewriting d/2 by a/2, we must rewrite it by

b/2.

We also must be careful to decide if right_sentinel should or not be

rewritten.

These kind of caveats open the window to bugs: what if we forget a rewrite?

For example, what about if b/2 uses null as an array marker instead of

nil that a/2 uses and we forget to rewrite right_sentinel properly?

Luckily propagating rewrites is a solved problem in rewriting systems, basically

you transverse the dependency graph and then apply rewrite from the bottom-up.

However, what is not a solved problem is to decide what rewrite is correct for

a particular setting.

We can think about a few options to narrow the window for bugs, for example we

can accept example files that describe the elements of the arrays and the

rewrite system reads these files to extract the elements.

We now have defined four predicates to concatenate two arrays depending on the

assumptions we make about them.

We draw our inspiration from an off-by-one error example from CWE, however,

conceptually there is no reason to assume the concatenation must be performed

from the 0 index, nor that it must be in increasing order.

We can start by generalizing array_length/1 to start counting from a given

offset.

The actual work, like in array_length/1 is done between afold/3 and

min_entry/5.

min_entry(Offset,RDomainMatch,a(N,RDomainMatch),undef,N):-

N >= Offset.

min_entry(_,RDomainMatch,a(N,RDomainMatch),Min,N):-

Min \== undef,

N < Min.

min_entry(Offset,RDomainMatch,a(Idx,D),Min,Min):-

D \== RDomainMatch.

Sometimes when we generalize we must be careful when we use these

generalizations because they usually carry a performance ticket.

The case of min_entry/5 raises the rewriting problem because is completely

plausible to consider the rewrite Offset --> 0 which would turn the first

clause body into N >= 0, and since arrays must be over an index set, that

inequality always holds which means the first clause can be redefined to:

min_entry(RDomainMathch,a(N,RdomainMathch),undef,N). which is the definition

used for concatenation.

That is, with a smarter rewrite we can obtain the efficient version for

concatenation from the general, more expressive but slower version avoiding us

to rewrite code or write specialized code.

Now that we can obtain the length of an array, we can start to design how we

should

join

two arrays.

If we do not impose any criteria to the order in which the join is performed,

then we must assume there exists a predicate position/2 that relates a position

in a/2 with a position in b/2.

The position/2 predicate would be user supplied, however this would imply

that all concatenation predicates we wrote to be generalized by one predicate

array_join/1 such that array_join(Pos):- bmap(Pos). which just forwards

the call to bmap/1.

This is not surprising since the actual concatenation is performed by bmap/1

and the calls before it are to set up the start position and the number of

elements to copy and the calls after to ensure array_length/1 continues to

work properly.

Hence, we overshoot with this proposal, because we are essentially renaming

bmap/1 which in our case is pointless.

Back to the offset initial idea, it should be easy to rewrite our different

array predicates to work with an offset.

It is also tempting to include a direction argument, for example calculate

the length of the array backwards.

However, at the current state of dfold/3 it is not possible to do it because

of how the d/2 predicates are fetched; but it seems to be a nice idea to

write dfold/4 which includes a predicate to pre-process the generated list

before folding it.

Another modification we can consider is to return the number of elements that

were actually copied.

This number is actually just a simple operation is most cases but this approach

becomes interesting if we also consider guarding the assignment of array

elements.

Imagine a single-threaded consumer-producer scenario in which we put

tasks/items in an array from another if we haven't seen them before and remove

the tasks/items at some point in time to make room for new tasks.

We can approach this scenario by using an extra array to hold the history of the

tasks/items we have seen so far and before adding a new task, we look into the

history and decide if we should add the task or not.

We can write a set of predicates to address this scenario, however, it can be

approached in a more general way by guarding each assignment.

Like callbacks and plug-ins, the user could define predicates to determine if an

entry can be set or not, these predicates must all succeed in order to allow the

modification.

This approach lets us to define independent conditions upon which we can act and

it is a cleaner design from our point of view.

We can model the previous scenario and any scenario in which a modification is

conditional without requiring custom code.

Once the client code is available it can be inlined by rewriting (a more

advanced version of our current rewriting) in order to avoid a few calls and

increase the performance.

[1] Monperrus,M., "Automatic Software Repair: A Bibliography",

ACM Computing Surveys, Volume 51, Issue 1, 2018

[2] Hoare, C. (ed.), Woodcock, J., Davies, J., "Using Z Specification, Refinement, and Proof", Prentice Hall International, 1996

[3] https://rocq-prover.org/

[4] Diller, A.,"Z An Introduction to Formal Methods, John Willey

and Sons, 2nd. Ed., 1994

[5] Craig,I., "Formal Models of Operating System Kernels",

Springer, 2007

[6] Craig,I., "Formal Refinement for Operating System Kernels",

Springer, 2007

[7] Hertzberg,N., et al., "CASP: An Evaluation Dataset for Formal

Verification of C Code", AISoLA, 2025

[8] Tihanyi, N., et al., "A New Era in Software Security: Towards

Self-Healing Software via Large Language Models and Formal Verification",

IEEE/ACM International Conference on Automation of Software, 2025

[9] Wang,W., et al., "Supporting Software Formal Verification with

Large Language Models: An Experimental Study", IEEE 33rd International

Requirements Engineering Conference, 2025

[10] Bertrand, N., et al., "Reusable Formal Verification of DAG-based

Consensus Protocols, LNCS 15682, NASA Formal Methods Symposium, 2025

[11] Norell, U., and Chapman, J, "Dependently Typed Programming in

Agda", Proceedings of the 4th international workshop on Types in language design

and implementation (TLDI '09), 2009

Copyright Alfredo Cruz-Carlon, 2025