Anote (Antoine's Notebook)

Because your creative process is not always linear nor explicable

A Version Control System is a manual or automatized system to track

changes to a set of files over time.

The main objective is to be able to (easily) recall past versions

[1].

Perhaps the most straight-forward approach to version control is

filename based versioning.

In it, the user makes copies of the file of interest and changes its name

in such a way that the new name contains enough information for the user

to identify the version.

For example, if you work on a proposal up to a

point where you are happy with the results and submit it for review,

it might be a good idea to save a copy of the submitted proposal with a

filename like submission_for_first_review.

This system might be get a bit tricky over time as the submit-review cycle

grows or branches. For example, if you have three reviewers giving

you feedback asynchronously you can either wait for all the reviews to

arrive and then apply all the changes or you can start to work on each

review as they arrive.

To keep track of the changes you could name your files

first_review_1st_reviewer_changes

and so on.

The aggregation of the files

first_review_1st_reviewer_changes,

first_review_2nd_reviewer_changes and

first_review_3rd_reviewer_changes

would yield the version submission_for_second_review.

Even if you only have self-review a similar process occurs and it is quite

possible to end up with meme-like names:

final_final_really_final_version.

Automatic version control systems like CVS, Subversion and Git lifts this

burden, the key concept is: save a snapshot of this.

You may give a description of the snapshot to explain why you took it,

and how or why the object you are tracking changed from its previous

version.

You can use these kind of systems locally for your work, I started to use

CVS and Subversion in the early 2000's and later Git;

If I'm going to create something that will change overtime, then I create

a git repository in my local server and clone copies on my work computers.

I feel protected in case of failure and the history of my repositories are

somewhat comprehensive.

But my personal relationship with git is one of love-hate.

Git has a plethora of features and what I'm going to describe here, namely,

Anote, can be fully (and better) simulated under Git, so if you will, Anote

can be seen as a trivial renaming of Git concepts and commands.

Arguably Git (and its flavors) is the de facto version control system; it

is fast, simple (in ideas), distributed, allows parallel development, and

can cope with big code-bases [1].

Git is designed to enhance collaboration between developers.

Developers must be able to communicate clearly in natural language, hence

the messages that come with changes must be (1) non empty and (2) clear.

If the developers in charge of modifying a Git repository are not convinced

of the value of the changes, then, said modification is rejected or asked

to be changed.

This communication loop is evident in what are known as

pull-requests.

A feature equivalently implemented by the Linux kernel community as

development mailing lists.

The natural language explanations of changes also known as commit messages,

are a valuable historic documentation resource.

Projects like the Linux kernel have strong formatting and guidelines to

write such messages.

When I look at a Git repository I can not avoid to have a linear

view of the development process, even if the repository has thousands of

branches, they all lead to the same place, the main/master branch.

No one in sane mind would keep alive work that was and will not be merged

into any significant branch.

This use of Git combined with strictly formatted and meaningful commit

messages tells a story of a finished product, a system evolving

steady.

I feel Git is designed as a Depth-first development story telling.

You start at some point, say v.0.1 and steadily evolve to v.0.2 and so on

to v.10.0 and beyond.

Each evolution comes with a Changelog explaining what has changed from the

last version to the current version.

This is a perfect way to tell a story over time.

Reading the Linux kernel commit history is like reading a book.

However, when I engage in creative, non-mechanical endeavors I want to:

(1) Keep a log of what I have done (2) Don't have to explain myself every

time and (3) Be able to seek inspiration from several previously tried

paths.

That is, I want to have a version system that is designed as a Breath-First

development story telling.

Anote is designed to track individual files over time with no clear

evolving structure whatsoever.

It is like our paper notebook, it is not meant to be understood by anyone

but us, we develop color codes, symbols, alignments and so on.

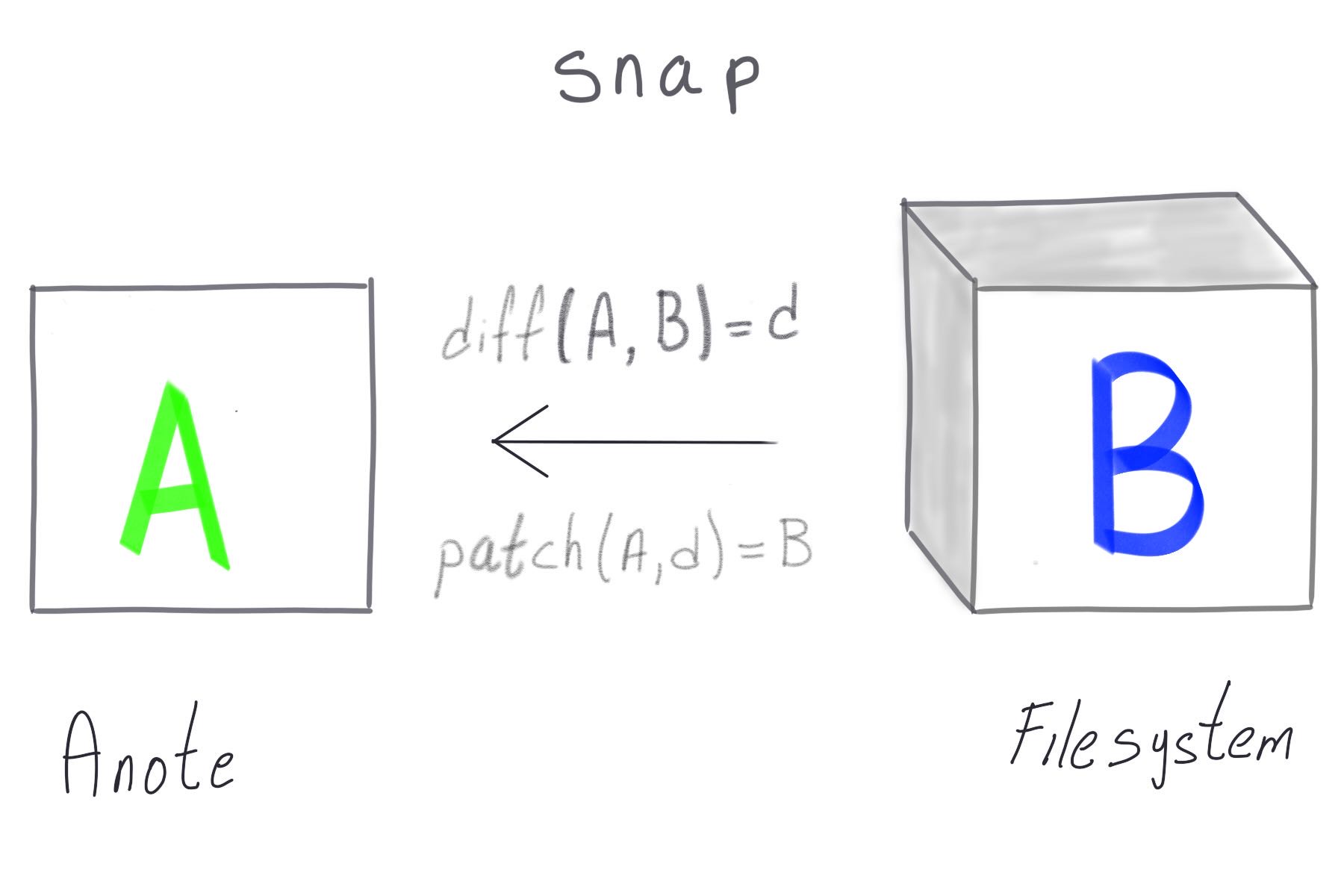

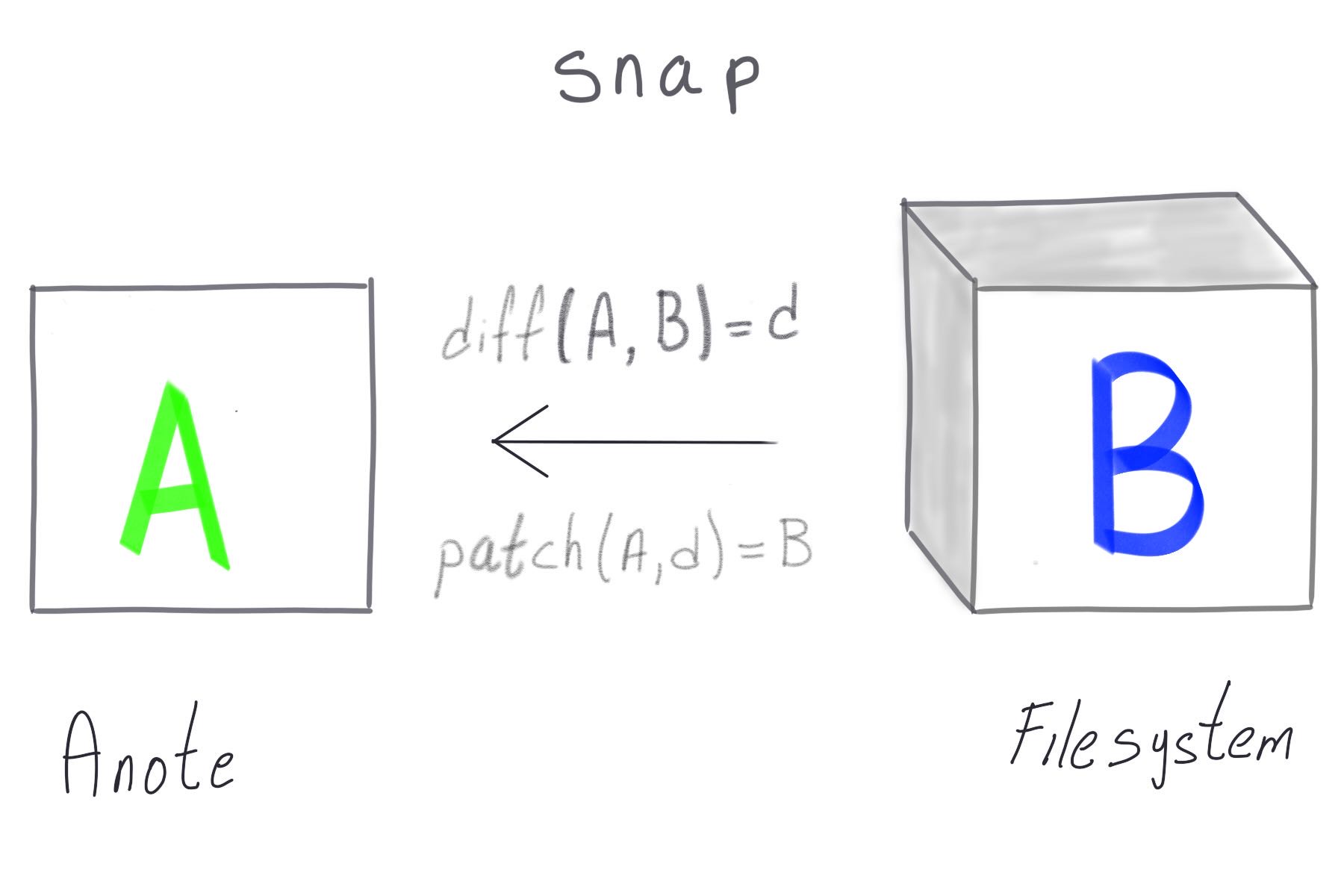

Anote basic block is the snapshot, that is, the action:

record this version.

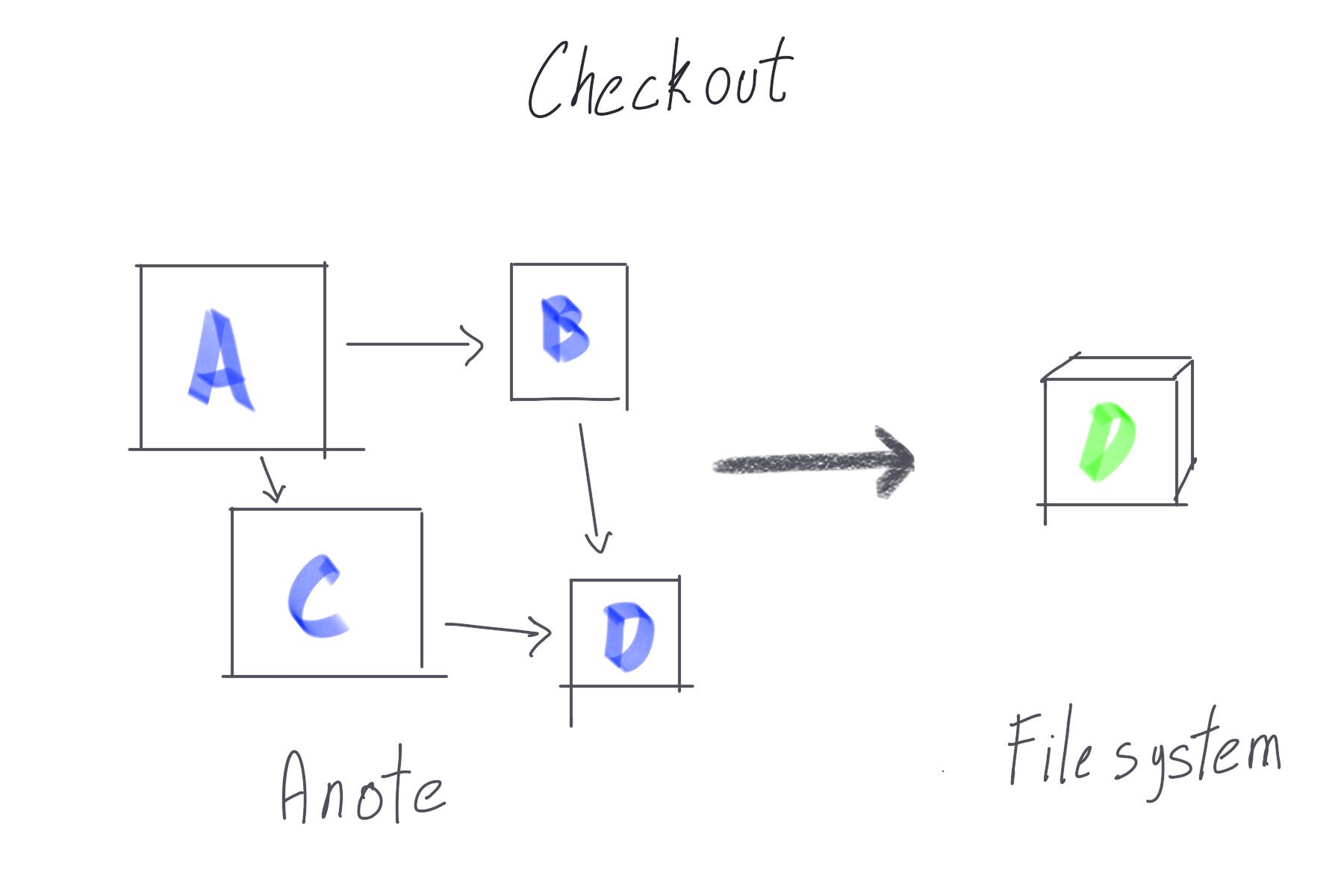

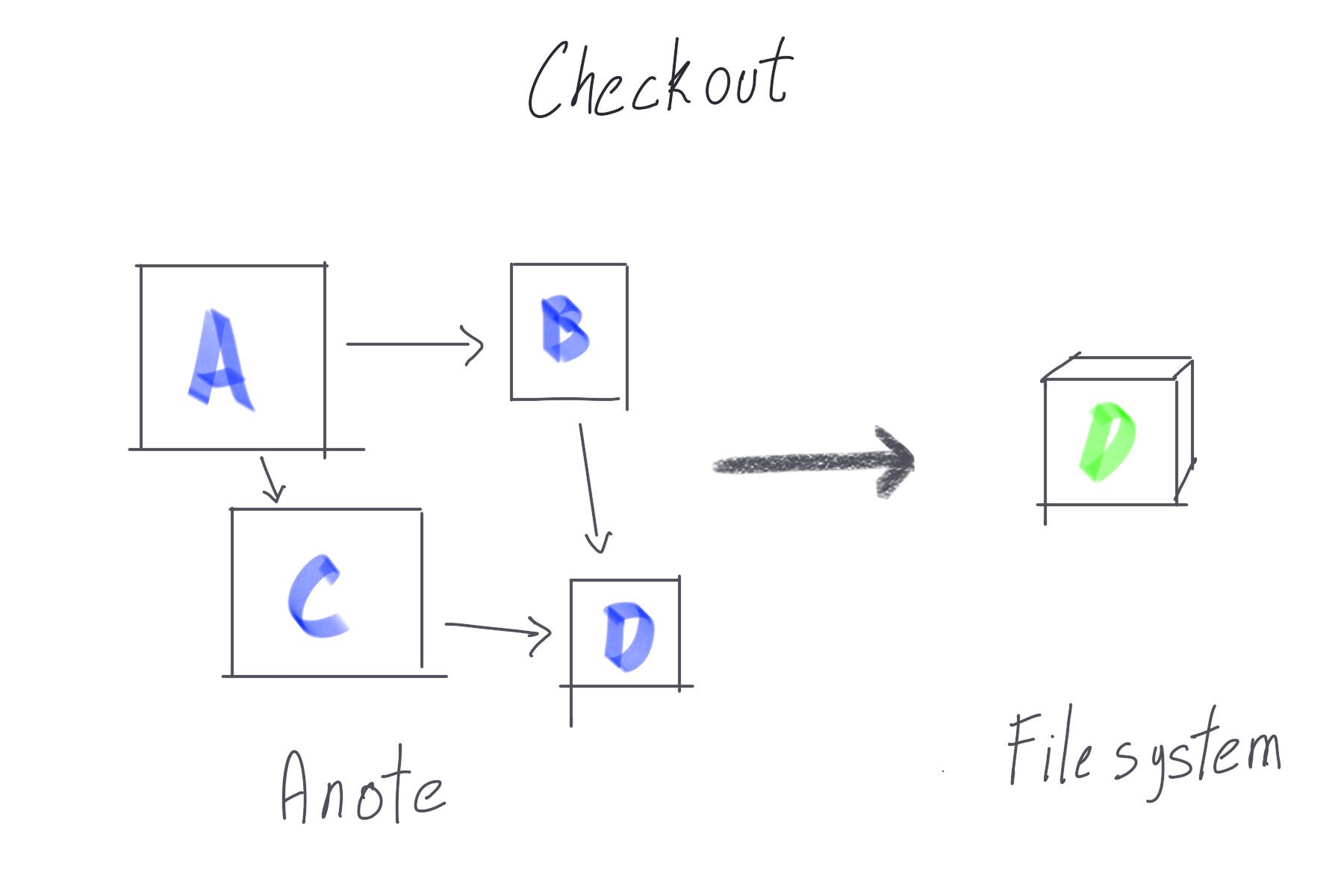

To recall previous versions Anote uses checkout to: recover this

version.

In its simplest form, Anote uses positive integers to distinguish

between versions.

When a snapshot is requested for a file, a

diff is taken between the last known

version and the current state of the file.

The last known version is either the last snapshot taken or a

checked out version.

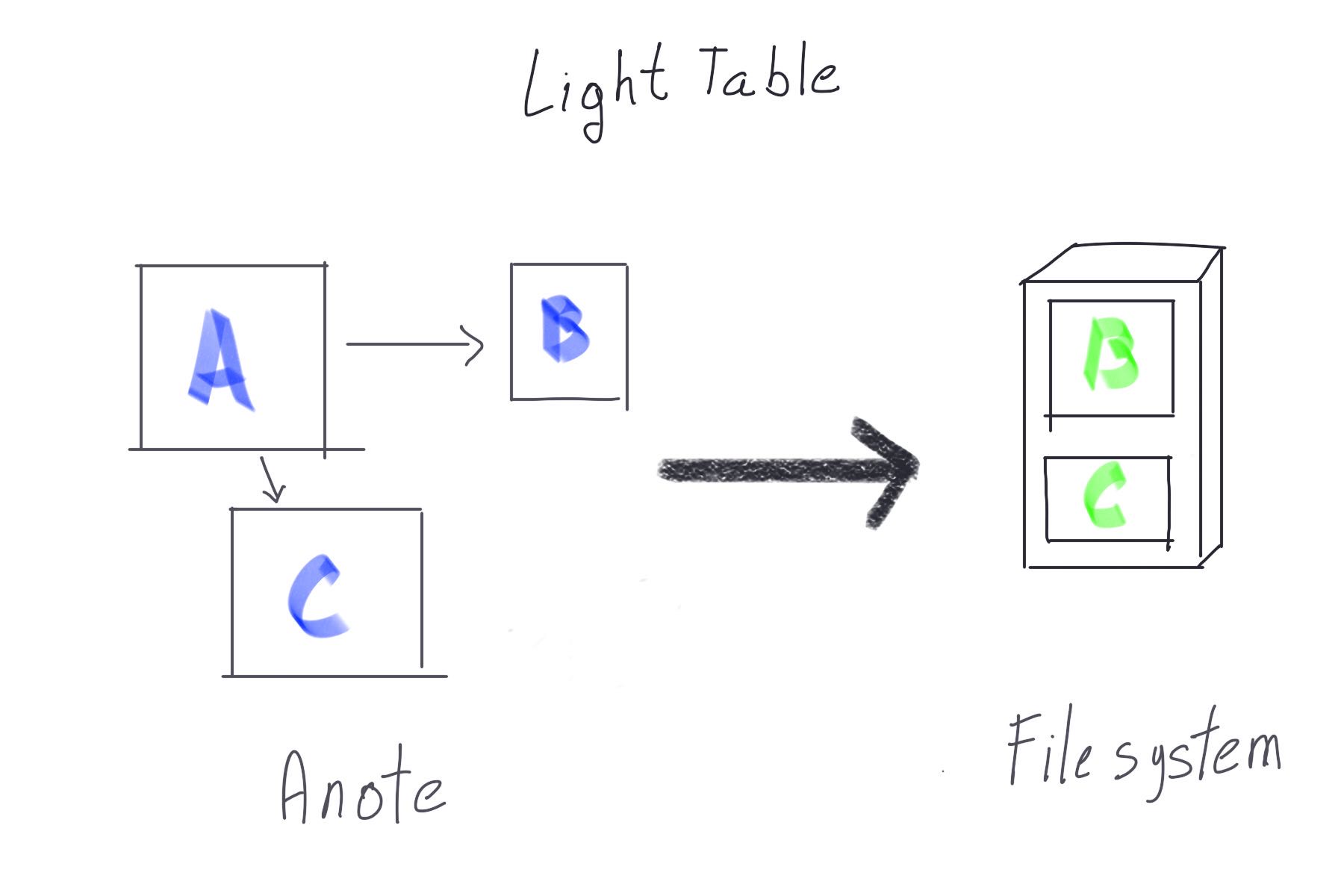

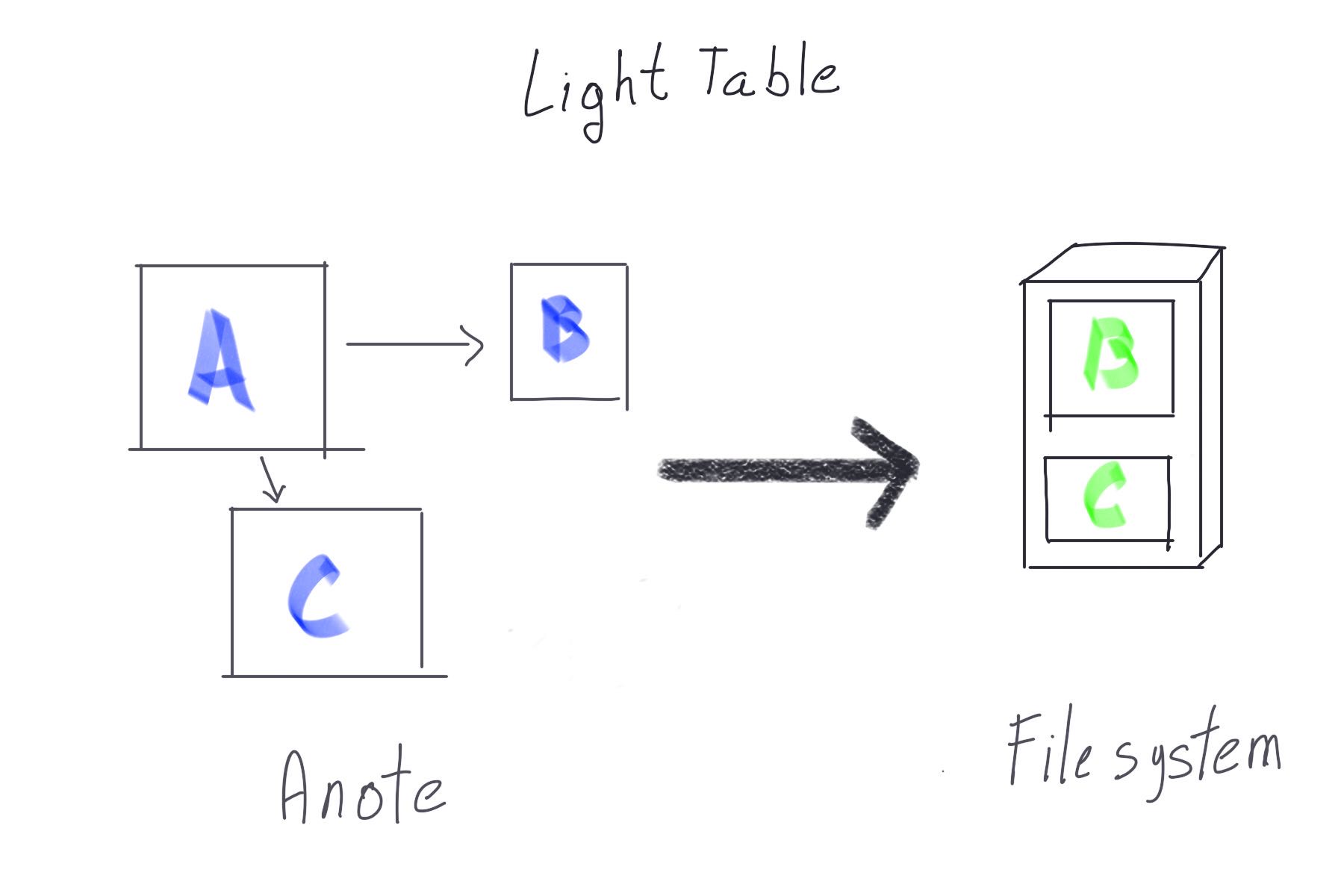

Anote supports the checkout of different versions at the same time, this is

called a Light Table to reference the light tables artists use to

put together artwork or review films.

Upon destruction of a Light Table, a snapshot

is taken and each checked out version in the Light Table is associated

with the new version.

The idea of a Light Table is to make explicit the collaboration required

to arrive at the version registered upon the Light Table's destruction.

The following drawings depict these three operations.

The arrows show the flow of information.

All these operations can be modeled with edge-labeled graphs.

The semantics of a "d" labeled AB arrow (

)

in Anote is: Version B was

created from Version A by applying the change "d".

In principle the semantics is not different from any version control

system, however, it allows the creation of unstructured graphs.

The path A → B → C → D depicts a sequence of

modifications much like a linear Git branch evolution.

The graph B ← A → C depicts a couple of branches

emerging from A.

Anote does not requires branches to be named, if a snapshot is taken of a

version that already has a successor, a new "branch" is created to

allocate the snapshot.

Conversely, the graph B → A ← C shows that creating A was a

collaboration between B and C.

There is no notion of conflict or merging, just

transformation and gluing.

Not requiring a message for snapshots or names for conceptual branches,

free us to name a version or explain it when we require it for our work,

not before.

Anote is designed to work independently of Git.

For example, if you require to patch a complicated bug, you may create a

new Git branch and track the file with Anote.

You may now modify the file back and forth, explore different fixes while

keeping track of the changes to later explore how to tidy up your work

into an elegant fix.

Once you are happy with the results then you are ready to commit to the

Git branch and have those changes merged into a testing branch.

Internally Anote works on diff files to represent a transformation, but

this approach might be inadequate for human-reviewing purposes.

Therefore, I envision modular expansion of Anote to accommodate external

parsers and report changes at a higher level of abstraction.

In early 2000's I bought a Spanish translation of the 50th anniversary

edition of Le petit prince (The little prince) by

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry.

The edition contains copies of annotated manuscripts that to me were a

treasure because Le petit prince is one of my all-time favorite

books.

This is the main reason for Anote name. But not the only one

During my time in Copenhagen, Denmark, like many I fell in love with

Ib Antoni's (the man who drew Denmark) designs.

An exhibit at the Museum of Copenhagen many of Ib's annotated designs and

notebooks were shown, again this shows all the work behind the finished

canvas.

So Anote can be as well read as: Antoni's Notebook, but since Antoine came

first to my life, history takes precedence.

Note: I refuse to call it AA's Notebook.

[1] Chacon, S. and Straub, B., "Pro Git", Apress, 2nd Ed., 2014.

Online version: https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2

(last accessed: March 16, 2025)

Copyright Alfredo Cruz-Carlon, 2025